GPU MODE Lecture 2: Ch.1-3 PMPP Book

- GPU MODE Lecture Notes: My notes from the GPU MODE reading group lectures run by Andreas Kopf and Mark Saroufim.

- Lecture Information

- Ch.1: Introduction

- Ch.2: Heterogeneous Data Parallel Computing

- Ch.3: Multidimensional Grids and Data

Lecture Information

Speaker: Andreas Kopf

Topic: PMPP Book Ch. 1-3

Resources:

Lecture Slides: CUDA Mode: Lecture 2

GitHub Repository: GPU MODE Lecture 2

Discord Channel: GPU MODE

YouTube Channel: GPU MODE

Introduction

- Timestamp: 1:00

Motivation

- Optimize GPU performance as much as possible

- Applications:

- simulate and model worlds

- games

- weather

- proteins

- robotics

- simulate and model worlds

- Bigger models are smarter

- speed and size improvements can have a significant impact on useability

- GPUs are the backbon of modern deep learning

History

- Classic software uses sequential programs

- executed one step at a time

- relied on higher CPU clock rates for improved performance

- Higher clock rate trend for CPUs slowed in 2003 due to energy consumption and heat dissipation challenges

- Increasing frequency would make the chip to hot to cool feasibly

- Multi-core CPU came up

- Developers had to learn multi-threading

- New challenges such as deadlocks and race conditions

- Developers had to learn multi-threading

Rise of CUDA

- Compute Unified Device Architecture

- CUDA is all about parallel programs

- divide work among threads

- GPUs have much higher peak FLOPS than multi-core CPUs

- Benefits highly parallelized programs

- Not suitable for largely sequential programs

- CPU+GPU

- Run sequential parts on CPU and numerically intensive parts on GPU

- GPGPU

- Before CUDA tricks were used to compute with graphics APIs like OpenGL and Direct3D

- GPU programming is now attractive to developers due to massive availability

Amdahl’s Law

\[ speedup = ( Slow \ System \ Time )/(Fast \ System \ Time) \]

achievable speedup is limited by the parallelizable portion of \(p\)

\[ speedup < \frac{1}{1-p} \]

- If \(p\) is \(90\%\), \(speedup < 10X\)

\(p > 99\%\) for many real applications

- especially for large datasets

- speedups \(> 100X\) are attainable

Challenges

- “If you do not care about performance, parallel programming is very easy”

- In practice, designing parallel algorithms is harder than sequential algorithms

- Parallelizing recurrent computations requires nonintuitive thinking

- prefix sum

- Parallelizing recurrent computations requires nonintuitive thinking

- Speed is often limited by memory latency/throughput (memory bound)

- Often need to read something to the GPU, perform some computation, and the write back the result

- LLM inference generates token by token

- Often need to read something to the GPU, perform some computation, and the write back the result

- Input data characteristics can significantly influence performance of parallel programs

- LLMs short or large sequences

- Might need different kernels optimized for different input shapes

- Not all applications are “embarrassingly parallel”

- Synchronization imposes overhead

- Need to wait for GPU operations to complete

- Synchronization imposes overhead

Main Goals of the Book

- Parallel programming & computational thinking

- Aims to build a foundation for parallel programming in general

- Uses GPUs as a learning vehicle

- Techniques apply to other accelerators

- Concepts are introduced through hands-on CUDA examples

- Correct & reliable parallel programing

- Debugging both functions and performance

- Understanding where things are fast and slow and how to improve the slow parts

- Scalability

- Regularize and localize memory access

- How to organize memory

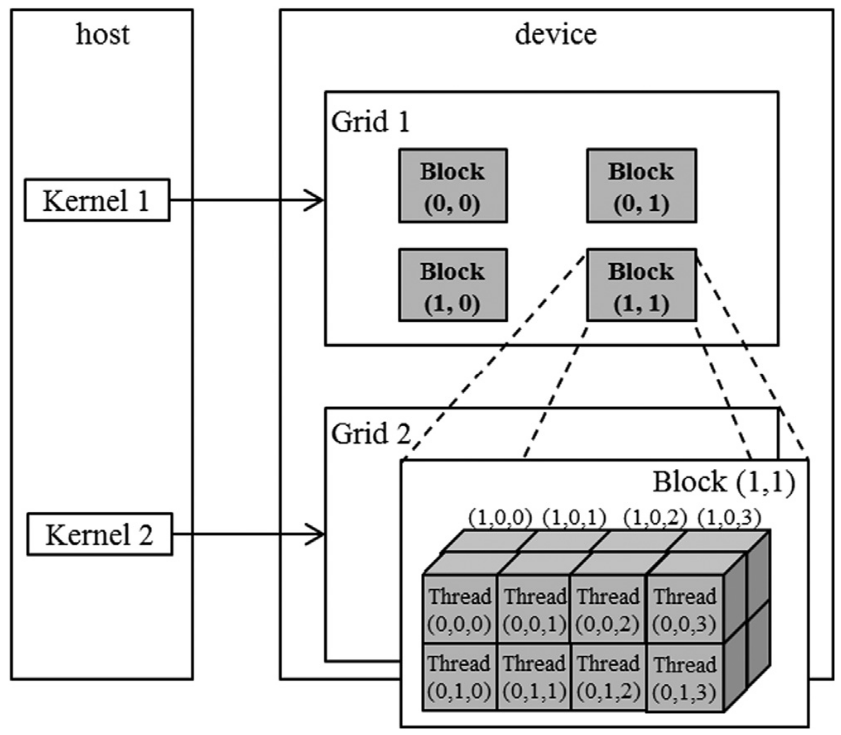

Heterogeneous Data Parallel Computing

- Timestamp: 8:31

- heterogeneous: CPU + GPU

- data parallelism: break work down into computations that can be executed independently

CUDA C

- extends ANSI C with minimal new syntax

- Terminology

- CPU=host

- GPU=device

- Kernels: device code functions

- CUDA C source can be a mixture of host & device code

- grid of threads

- Many threads are launched to execute a kernel

- CPU & GPU code runs concurrently (overlapped)

- Kernels launch and run on GPU asynchronously

- Need to wait for the kernels to finish before copying data back to CPU

- Don’t be afraid to launch many threads on GPU

- One thread per output tensor is fine

CUDA Essentials: Memory Allocation

- NVIDIA devices come with their own DRAM (device) global memory

cudaMalloc&cudaFree:cudaMalloc: Allocate device global memorycudaFree: Free device global memoryfloat *A_d; size_t size = n * sizeof(float); // size in bytes cudaMalloc((void**)&A_d, size); // pointer to pointer ... cudaFree(A_d);Code convention

_dfor device pointer_hfor host

cudaMemcpy- Copy data from CPU memory to GPU memory and vice versa

// copy input vectors to device (host -> device) cudaMemcpy(A_d, A_h, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); cudaMemcpy(B_d, B_h, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); ... // transfer result back to CPU memory (device -> host) cudaMemcpy(C_h, C_d, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

CUDA Error Handling

- CUDA functions return

cudaError_tcudaSuccessfor successful operation

- Always check returned error status

Kernel functions fn<<>>

- Launching kernel

- grid of threads is launched

- All threads execute the same code

- SPMD: Single Program Multiple Data

- Threads are hierarchically organized into grid blocks & thread blocks

- Up to 1024 threads in a thread block

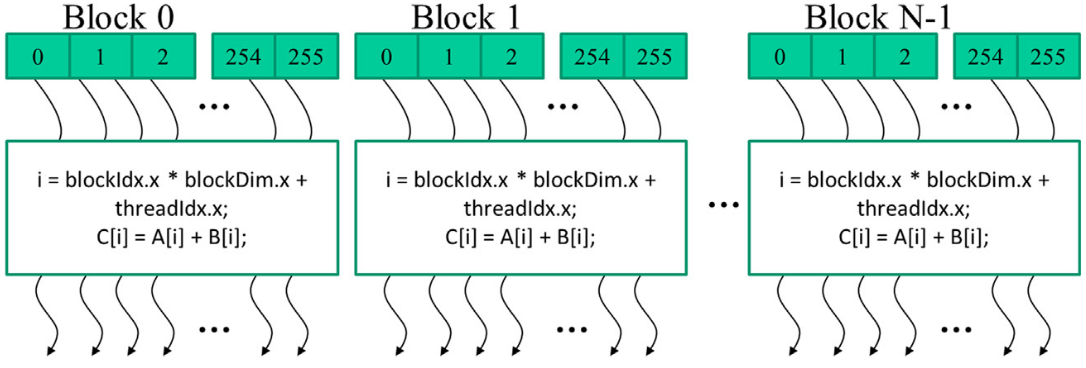

Kernel Coordinates

- Built-in variables available inside the kernel

blockIdx: the area code for a telephone- Note: Blocks are a logical organization of threads, not physical

threadIdx: the local phone number- These are ‘coordinates’ that allow threads to identify which portion of the data to process

- Can use

blockIdxandthreadIdxto uniquely identify threads blockDim: tells us the number of threads in a block

- For vector addition, we can calculate the array index of the thread

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

- All threads in a grid execute the same kernel code

CUDA C keywords for function declaration

| Qualifier Keyword | Callable From | Executed On | Executed By |

|---|---|---|---|

__host__ (default) |

Host | Host | Caller host thread |

__global__ |

Host (or Device) | Device | New grid of device threads |

__device__ |

Device | Device | Caller device thread |

__global__&__host__- Tell the compiler whether the function should live on the device or host

- Declare a kernel function with

__global__- Calling a

__global__function launches new grid of CUDA threads

- Calling a

- Functions declared with

__device__can be called from within CUDA thread- Does not launch a new thread

- Only accessible from within kernels

- If both

__host__and__device__are used in a function declaration- CPU and GPU versions will be compiled

Calling Kernels

- Kernel configuration is specified between

<<<and>>> - Number of blocks, number of threads in each block

// Define the number of threads per block. // Each block will have 256 threads. dim3 numThreads(256); // Calculate the number of blocks needed to cover the entire vector. // Use ceiling division to ensure that the number of blocks is sufficient // to handle all elements of the vector 'n'. // The formula (n + numThreads.x - 1) / numThreads.x ensures this. dim3 numBlocks((n + numThreads.x - 1) / numThreads.x); // Launch the vector addition kernel with the calculated number of blocks and threads. // This will execute the vecAddKernel function on the GPU with 'numBlocks' blocks, // each containing 'numThreads.x' threads. vecAddKernel<<<numBlocks, numThreads>>>(A_d, B_d, C_d, n);

Compiler

- nvcc

- NVIDIA C Compiler

- Use to compiler kernels into PTX (CUDA assembly)

- PTX

- Parallel Thread Execution

- Low-level VM & instruction set

- Grahics driver translates PTX into executable binary code (SASS)

- SASS is the low-level assembly language that compiles to binary microcode, which executes natively on NVIDIA GPU hardware.

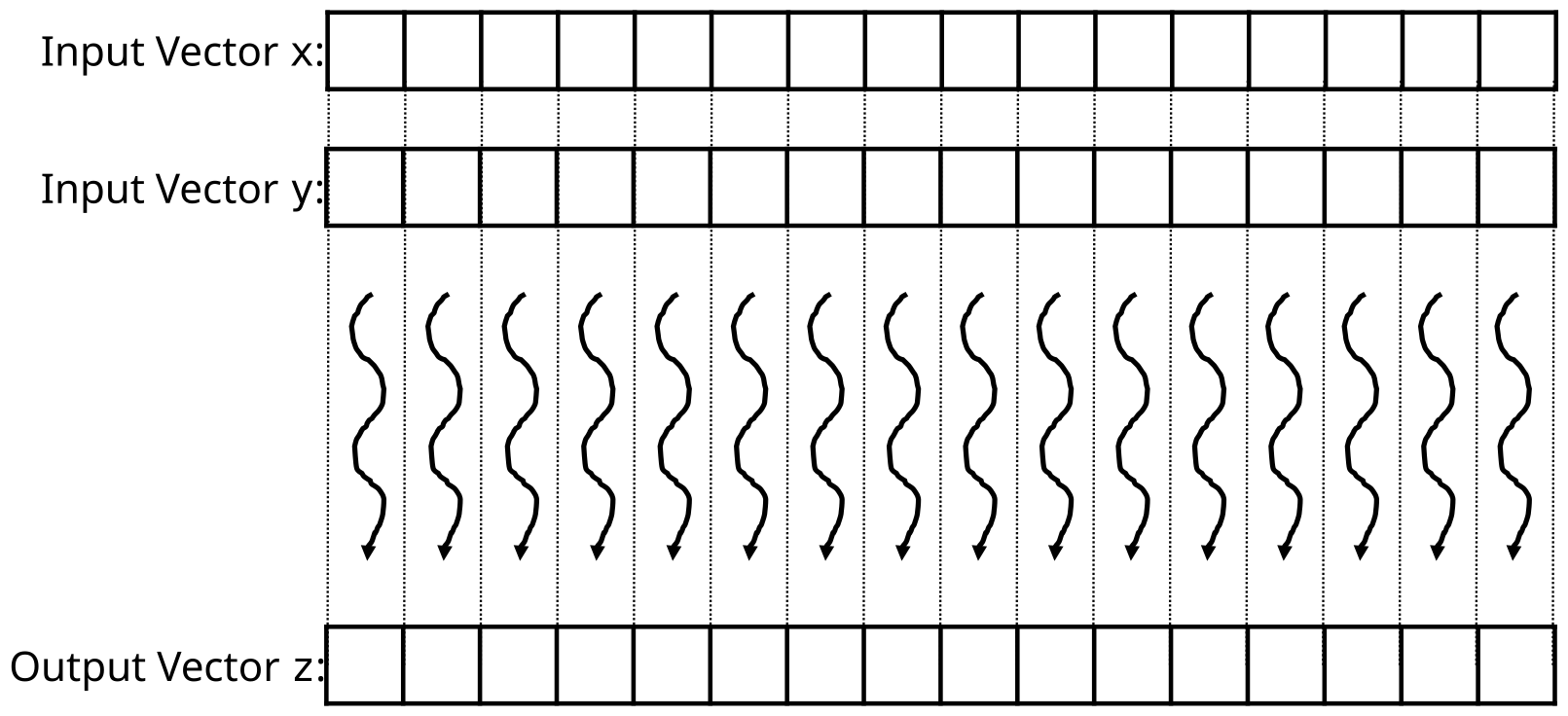

Code Example: Vector addition

- main concept: replace loop with a grid of threads

- easily parallelizable

- all additions can be computed independently

- Naive GPU vector addition

- Allocate device memory for vectors

- Transfer inputs from host to device

- Launch kernel and perform addition operations

- Copy outputs from device to host

- Free device memory

- The ratio of data transfer vs compute is not very good

- Normally keep data on the GPU as long as possible to asynchronously schedule many kernel launches

- Figure from slide 13:

- One thread per vector element

- One thread per vector element

- Data sizes might not be perfectly divisible by block sizes

- always check bounds

- Prevent threads of boundary block to read/write outside allocated memory

/** * @brief CUDA kernel to compute the element-wise sum of two vectors. * * This kernel function performs the pair-wise addition of elements from * vectors A and B, and stores the result in vector C. * * @param A Pointer to the first input vector (array) in device memory. * @param B Pointer to the second input vector (array) in device memory. * @param C Pointer to the output vector (array) in device memory. * @param n The number of elements in the vectors. */ __global__ void vecAddKernel(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) { // Calculate the unique index for the thread int i = threadIdx.x + blockDim.x * blockIdx.x; // Check if the index is within the bounds of the arrays if (i < n) { // Perform the element-wise addition C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } }

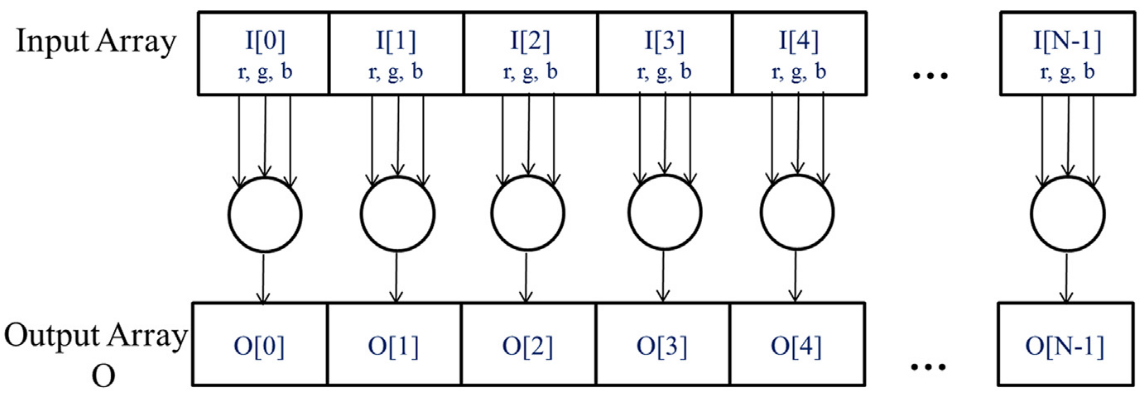

Code Example: Kernel to convert an RGB image to grayscale

- Each RGB pixel can be converted individually

- \[ Luminance = r\cdot{0.21} + g\cdot{0.72} + b\cdot{0.07} \]

- Simple weighted sum

Multidimensional Grids and Data

- Timestamp: 24:55

CUDA Grid

- 2-level hierarchy

- Blocks and threads

- Idea: Map threads to multi-dimensional data (e.g., an image)

- All threads in a grid execute the same kernel

- Threads in the same block can access the same shared memory

- Max block size: 1024

- Built-in 3D coordinates of a thread

blockIdxandthreadIdxidentify which portion of the data to process

- shape of grid & blocks

gridDim: number of blocks in the gridblockDim: number of threads in a block

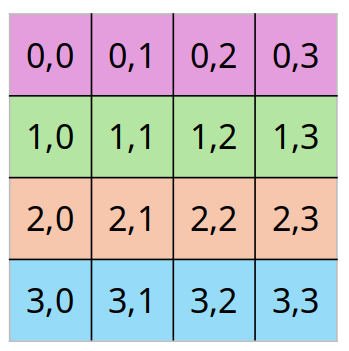

- A multidimensional example of CUDA grid organization:

- Grid can be different for each kernel launch

- Normally dependent on data shapes

- Typical grids contain thousands to millions of threads

- Simple Strategy

- One thread per output element

- One thread per pixel

- One thread per tensor element

- One thread per output element

- Threads can be scheduled in any order

- A larger thread index does not necessarily indicate the thread is running after a thread with a lower index

- Can use fewer than 3 dims (set others to 1)

- 1D for sequences, 2D for images, etc.

dim3 grid(32, 1, 1); dim3 block(128, 1, 1); kernelFunction<<<grid, block>>>(..); // Number of threads: 128*32 = 4096

Built-in Variables

- Built-in variables inside kernels:

blockIdx // dim3 block coordinate threadIdx // dim3 thread coordinate blockDim // number of threads in a block gridDim // number of blocks in a gridblockDimandgridDimhave the same values in all threads

nd-Arrays in Memory

- memory of multi-dim arrays under the hood is a flat 1-dimensional array

- 2d array can be linearized in different ways

A B C D E F G H I- row-major

A B C D E F G H I- Most common

- column-major

A D G B E H C F I- Used in fortran

- PyTorch tensors and numpy arrays use strides to specify how elements are laid out in memory

- For a \(4 \times 4\) matrix, the stride would be \(4\) to get to the next row.

- After four elements, you end up in the next row.

- For a \(4 \times 4\) matrix, the stride would be \(4\) to get to the next row.

Code Example: Image Blur

- mean filter example

blurKernel:// CUDA kernel to perform a simple box blur on an input image __global__ void blurKernel(unsigned char *in, unsigned char *out, int w, int h) { // Calculate the column and row index of the pixel this thread is processing int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; // Ensure the thread is within the image bounds if (col < w && row < h) { int pixVal = 0; // Variable to accumulate the sum of pixel values int pixels = 0; // Variable to count the number of valid pixels in the blur region // Loop over the surrounding pixels within the blur region for (int blurRow = -BLUR_SIZE; blurRow <= BLUR_SIZE; ++blurRow) { for (int blurCol = -BLUR_SIZE; blurCol <= BLUR_SIZE; ++blurCol) { int curRow = row + blurRow; // Current row index in the blur region int curCol = col + blurCol; // Current column index in the blur region // Check if the current pixel is within the image bounds if (curRow >= 0 && curRow < h && curCol >= 0 && curCol < w) { pixVal += in[curRow * w + curCol]; // Accumulate the pixel value ++pixels; // Increment the count of valid pixels } } } // Calculate the average pixel value and store it in the output image out[row * w + col] = (unsigned char)(pixVal / pixels); } }

- each thread writes one output element, read multiple values

- single plane in book, can be easily extended to multi-channel

- shows row-major pixel memory access (in & out pointers)

- track of how many pixel values are summed

- Handling boundary conditions for pixels near the edges of the image:

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np

from PIL import Image

import torch

from torch.utils.cpp_extension import load_inline#include <torch/types.h>

#include <cuda.h>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

#include <c10/cuda/CUDAException.h>

#include <c10/cuda/CUDAStream.h>

// CUDA kernel for applying a mean filter to an image

__global__

void mean_filter_kernel(unsigned char* output, unsigned char* input, int width, int height, int radius) {

// Calculate the column, row, and channel this thread is responsible for

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int channel = threadIdx.z;

// Base offset for the current channel

int baseOffset = channel * height * width;

// Ensure the thread is within image bounds

if (col < width && row < height) {

int pixVal = 0; // Accumulator for the pixel values

int pixels = 0; // Counter for the number of pixels summed

// Iterate over the kernel window

for (int blurRow = -radius; blurRow <= radius; blurRow += 1) {

for (int blurCol = -radius; blurCol <= radius; blurCol += 1) {

int curRow = row + blurRow;

int curCol = col + blurCol;

// Check if the current position is within image bounds

if (curRow >= 0 && curRow < height && curCol >= 0 && curCol < width) {

// Accumulate pixel value and count the number of pixels

pixVal += input[baseOffset + curRow * width + curCol];

pixels += 1;

}

}

}

// Write the averaged value to the output image

output[baseOffset + row * width + col] = (unsigned char)(pixVal / pixels);

}

}

// Helper function for ceiling unsigned integer division

inline unsigned int cdiv(unsigned int a, unsigned int b) {

return (a + b - 1) / b;

}

// Main function to apply the mean filter to an image using CUDA

torch::Tensor mean_filter(torch::Tensor image, int radius) {

// Ensure the input image is on the GPU, is of byte type, and radius is positive

assert(image.device().type() == torch::kCUDA);

assert(image.dtype() == torch::kByte);

assert(radius > 0);

// Get image dimensions and number of channels

const auto channels = image.size(0);

const auto height = image.size(1);

const auto width = image.size(2);

// Create an empty tensor to store the result

auto result = torch::empty_like(image);

// Define the number of threads per block and number of blocks

dim3 threads_per_block(16, 16, channels);

dim3 number_of_blocks(

cdiv(width, threads_per_block.x),

cdiv(height, threads_per_block.y)

);

// Launch the CUDA kernel

mean_filter_kernel<<<number_of_blocks, threads_per_block, 0, torch::cuda::getCurrentCUDAStream()>>>(

result.data_ptr<unsigned char>(),

image.data_ptr<unsigned char>(),

width,

height,

radius

);

// Check for any CUDA errors (calls cudaGetLastError())

C10_CUDA_KERNEL_LAUNCH_CHECK();

// Return the filtered image

return result;

}# Define the CUDA kernel and C++ wrapper

cuda_source = '''

#include <c10/cuda/CUDAException.h>

#include <c10/cuda/CUDAStream.h>

// CUDA kernel for applying a mean filter to an image

__global__

void mean_filter_kernel(unsigned char* output, unsigned char* input, int width, int height, int radius) {

// Calculate the column, row, and channel this thread is responsible for

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int channel = threadIdx.z;

// Base offset for the current channel

int baseOffset = channel * height * width;

// Ensure the thread is within image bounds

if (col < width && row < height) {

int pixVal = 0; // Accumulator for the pixel values

int pixels = 0; // Counter for the number of pixels summed

// Iterate over the kernel window

for (int blurRow = -radius; blurRow <= radius; blurRow += 1) {

for (int blurCol = -radius; blurCol <= radius; blurCol += 1) {

int curRow = row + blurRow;

int curCol = col + blurCol;

// Check if the current position is within image bounds

if (curRow >= 0 && curRow < height && curCol >= 0 && curCol < width) {

// Accumulate pixel value and count the number of pixels

pixVal += input[baseOffset + curRow * width + curCol];

pixels += 1;

}

}

}

// Write the averaged value to the output image

output[baseOffset + row * width + col] = (unsigned char)(pixVal / pixels);

}

}

// Helper function for ceiling unsigned integer division

inline unsigned int cdiv(unsigned int a, unsigned int b) {

return (a + b - 1) / b;

}

// Main function to apply the mean filter to an image using CUDA

torch::Tensor mean_filter(torch::Tensor image, int radius) {

// Ensure the input image is on the GPU, is of byte type, and radius is positive

assert(image.device().type() == torch::kCUDA);

assert(image.dtype() == torch::kByte);

assert(radius > 0);

// Get image dimensions and number of channels

const auto channels = image.size(0);

const auto height = image.size(1);

const auto width = image.size(2);

// Create an empty tensor to store the result

auto result = torch::empty_like(image);

// Define the number of threads per block and number of blocks

dim3 threads_per_block(16, 16, channels);

dim3 number_of_blocks(

cdiv(width, threads_per_block.x),

cdiv(height, threads_per_block.y)

);

// Launch the CUDA kernel

mean_filter_kernel<<<number_of_blocks, threads_per_block, 0, torch::cuda::getCurrentCUDAStream()>>>(

result.data_ptr<unsigned char>(),

image.data_ptr<unsigned char>(),

width,

height,

radius

);

// Check for any CUDA errors (calls cudaGetLastError())

C10_CUDA_KERNEL_LAUNCH_CHECK();

// Return the filtered image

return result;

}

'''

cpp_source = "torch::Tensor mean_filter(torch::Tensor image, int radius);"build_dir = Path('./load_inline_cuda')

build_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)# Load the defined C++/CUDA extension as a PyTorch extension.

# This enables using the `mean_filter` function as if it were a native PyTorch function.

mean_filter_extension = load_inline(

name='mean_filter_extension', # Unique name for the extension

cpp_sources=cpp_source, # C++ source code containing the CPU implementation

cuda_sources=cuda_source, # CUDA source code for GPU implementation

functions=['mean_filter'], # List of functions to expose to Python

with_cuda=True, # Enable CUDA support

extra_cuda_cflags=["-O2"], # Compiler flags for optimizing the CUDA code

build_directory=str(build_dir), # Directory to store the compiled extension

)# Define the path to the image file

img_path = Path('./Grace_Hopper.jpg')

# Open the image using PIL (Python Imaging Library)

test_img = Image.open(img_path)

test_img

# Convert the image to a NumPy array, then to a PyTorch tensor

# Rearrange the tensor dimensions from (H, W, C) to (C, H, W) and move it to GPU

x = torch.tensor(np.array(test_img)).permute(2, 0, 1).contiguous().cuda()

# Apply the mean filter to the tensor using a kernel size of 8

y = mean_filter_extension.mean_filter(x, 8)# Convert the filtered tensor back to a NumPy array, rearrange dimensions back to (H, W, C)

# and create an image from the array using PIL

output_img = Image.fromarray(y.cpu().permute(1, 2, 0).numpy())

output_img

Matrix Multiplication

- Staple of science, engineering, and deep learning

- Computer inner-products of rows and columns

- Strategy: 1 thread per output matrix element

- Example: Multiplying square matrices (rows == cols)

/** * @brief Matrix multiplication kernel function. * * This kernel performs the multiplication of two matrices M and N, storing the result in matrix P. * * @param M Pointer to the first input matrix. * @param N Pointer to the second input matrix. * @param P Pointer to the output matrix. * @param Width The width of the input and output matrices (assuming square matrices). */ __global__ void MatrixMulKernel(float* M, float* N, float* P, int Width) { // Calculate the row index of the P matrix element and M matrix element int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; // Calculate the column index of the P matrix element and N matrix element int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // Ensure that row and column indices are within bounds if ((row < Width) && (col < Width)) { float Pvalue = 0; // Initialize the output value for element P[row][col] // Perform the dot product of the row of M and column of N for (int k = 0; k < Width; ++k) { Pvalue += M[row * Width + k] * N[k * Width + col]; } // Store the result in the P matrix P[row * Width + col] = Pvalue; } }

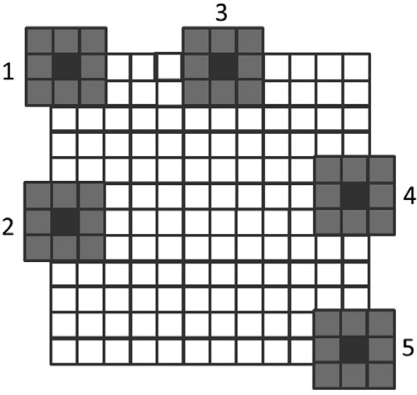

- Matrix multiplication using multiple blocks by tiling P:

I’m Christian Mills, an Applied AI Consultant and Educator.

Whether I’m writing an in-depth tutorial or sharing detailed notes, my goal is the same: to bring clarity to complex topics and find practical, valuable insights.

If you need a strategic partner who brings this level of depth and systematic thinking to your AI project, I’m here to help. Let’s talk about de-risking your roadmap and building a real-world solution.

Start the conversation with my Quick AI Project Assessment or learn more about my approach.